Background to Rebellion

Population

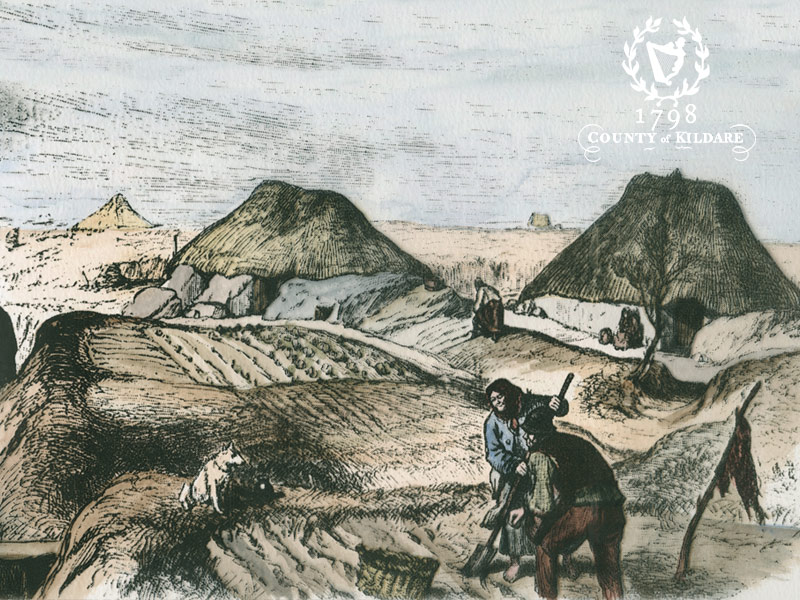

During the second half of the 18th century the population of Ireland almost doubled from around 2½ to just under 5 million. The vast majority of this growing population depended on land for a livelihood. The pressure on land tended to push up rents and encourage sub-division of holdings. This had a profound effect on rural society and most especially on the lowest classes who formed a high proportion of the total population. The hardships of the small holder and cottier classes were increased, for wages did not rise in proportion to rents and the general cost of living. For many, their only defence against such oppression lay in secret combination. Over much of the country there was an increase in the spread of secret societies.

After 1760 outbreaks of violence were common. Those involved were concerned with local issues such as rents, taxes and tithe payments. The payment of tithes which were dues payable to the local clergy of the established church by tenants irrespective of their own religion, were particularly resented. For the poor it presented more difficulty as a tithe, by the 1760s, was a transaction that had to be settled in cash. Dissenters, the majority of which were Presbyterians who had settled in the north east were compelled by law to pay tithes.

The Catholic upper classes like their Protestant neighbours wanted political power. Also there was an emerging Catholic middle class who were hoping for emancipation. They too wished to participate in law and politics.

Every decade from 1760 to 1800 was marred by outbreaks of violence, popularly or generically termed Whiteboyism. These ‘Midnight Legislators’ sought to redress their grievances by the use of terror – midnight raids, burnings, torture and even murder. A more ominous threat to law and order developed with the sectarian violence that erupted between the Peep O’ Day Boys and the Defenders in Armagh and Ulster in the late 1780s early 1790s, and the subsequent foundation of the Orange Order in 1795.

When the United Irishmen were suppressed by the government in 1794, their leaders realised they needed to develop a broader more popular basis to achieve their objectives and to spread their republican message. Links were forged with the Defenders and the two movements merged in 1795-6 as plans were made to break the connection with Britain by force of arms.