Background to Rebellion

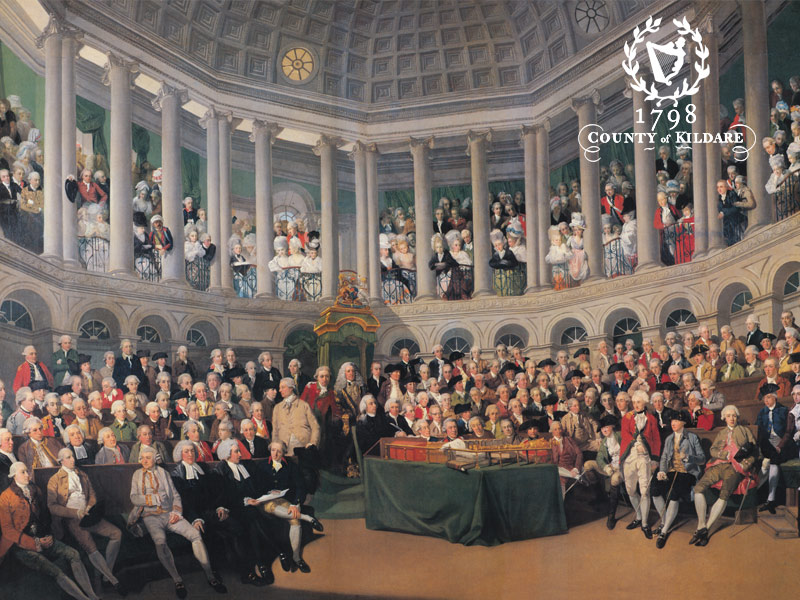

Grattan’s Parliament

Between 1692 and 1784 the Irish parliament sat for approximately six months every two years and annually thereafter. Both Poynings’ Law and the Declaratory Act circumscribed the Parliaments power. The head of the Irish executive the Lord Lieutenant who was a nominee of the British government lived here only while the Parliament was sitting.

Because of the absence of the Lord Lieutenant, the day to day business of administration was usually shared between office holders who were English born, and Irish politicians who were called undertakers, who had agreed to manage parliament on the Lord Lieutenants behalf.

When Lord Townsend decided to become a residential Lord Lieutenant in the late 1760s, the ‘patriots’ emerged. Inspired by the American Revolution of 1776, the patriot element demanded an end to the direct control which Westminster exercised over Irish legislation. The patriots were backed by a 40,000 strong volunteer force and in 1782 the British Government gave way to their demands. The offspring of the settlement, ‘Grattan’s Parliament’.

Henry Grattan entered Parliament as the member for the borough of Charlemont, Co. Armagh, in 1775 and soon became the acknowledged leader of the opposition, a role previously filled by Henry Flood. In 1782 he was instrumental in forcing the English Government to acknowledge the right of the Irish Parliament to operate as an independent legislature subject only to the Crown. In recognition of his contribution later historians established the custom of referring to the Parliament of the years 1782 to 1800 as Grattan’s Parliament even though after 1782 Grattan’s influence was limited and he in no sense controlled or directed Parliament. In fact while Parliament was now in theory independent in practice it was still controlled by the English government which continued to exercise its influence through the borough patrons. Grattan’s efforts in this supposedly free Parliament met with such opposition that he retired frustrated in 1797, returning only in 1800 to oppose the Union.

The Declaratory Act of 1719: Made the House of Lords at Westminster the final court of legal appeal in Irish law cases and gave the British Parliament the power to make law for Ireland.

Poynings Law 1494: This gave the English Privy Council the power to respite and to amend all legislation emanating from the Irish Parliament.