By Robert Stevick. (Provided by Monasterevin Historical Society)

The enigmatic ‘Monasterevin-type discs’ have been puzzling enough, and this short report may only add to their mystery rather than reduce it.

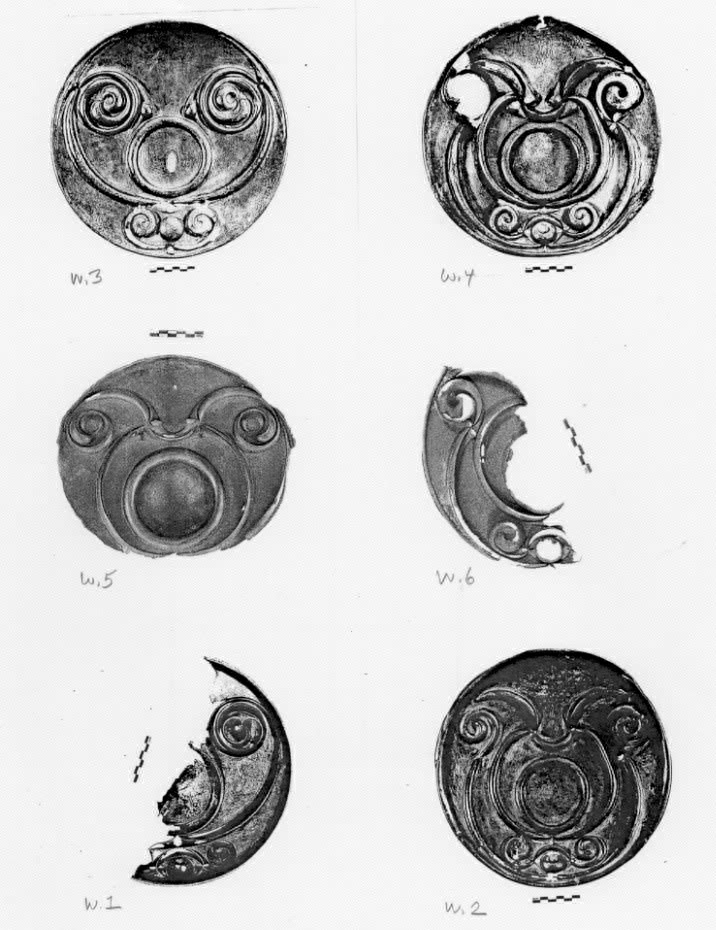

Of the seven distinctive bronze discs dated to the 1st or 2nd century A.D. and unique to Ireland, two are known to have been found at Monasterevin, while the find-place of the others is undocumented (hence the label ‘Monasterevin-type’). Six of them are now in the National Museum, Dublin, the seventh in the British Museum, London.

Professor Barry Raferty provides detailed descriptions as well as discussion of their affinities and chronology in La Tene in Ireland. Basically, they are bronze sheets hammered into the form of discs the size of a dinner plate (10-11 inches, 25-30cm. ) by a technique now called repousse. ‘A feature common to all discs is a plain, eccentrically-placed circular area defined in every case by a raised ring of rounded section’. All have paired snail-shell spirals. And so on. They are all of a type, yet no two are identical. Guesses about their purpose range from ornamental to ritual to solar symbolism to portions of shields.

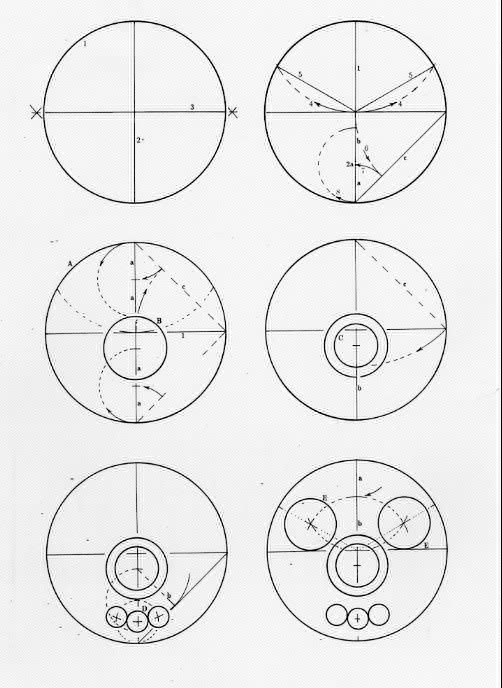

There is no guess-work, though about how their forms wee devised. A compass is employed not only for drawing the circles, but for determining exactly where the inner circles are located, as well. Spirals and arcs accommodate to the circles. Several of the pieces have been crafted so accurately that there can be no doubt about the principles of their layout. See the drawing below.

All are circular, so begin by drawing a circle (1).

All are bilaterally symmetrical, so draw a line (a diameter) through its centre (2); all develop ‘geometrical’ measures found in simple right triangles, so set a second diameter perpendicular to the first one (3).

All have paired circular areas from which arise opposing spirals, whose centres are always located along the same line: set the fixed point of the compass at one end of the first diameter, and with the same radius as the circle, mark two points on the circle (4); these circular areas have centres located along lines between the centre of the disc and these two points (5).

No fewer than five of the seven discs locate the centres of the ‘eccentrically-placed circular’ are in exactly the same place (relative to the outer circle): one simple procedure is shown (6-7-8). The other two have slight variants of this.

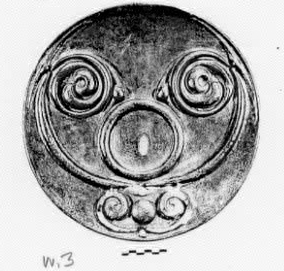

Upon this cantus firmus, plans for the separate pieces are then devised. The rest of the drawing illustrates the evolution of one (W.3, see image below) normally on display in the National Museum. The key to its coherent geometry is this: let 1 be the measure of the radius of the disc, c the length of the chord of a quadrant; then a is 1 less than c, and b is a less than 1. See the table. (In modern terms, c = Ö 2.) With these linked measures (1, 2, c, a, b) and no others the circular ares of this disc are assigned their places. (Alternate methods are shown for plotting circles E are shown with dashed and dotted lines.).

|

Circle A. |

Radius: Diameter: |

1 2 |

|

Circle B. |

Top: Centre: |

2a from bottom of circle A 2a from bottom of circle A |

|

Circle C. |

Centre: Bottom: |

2a from bottom of circle A 2a from top of circle A or b from bottom of circle A |

|

Circle D. |

Centre: Bottom: |

b belowcentre of cicles B and C; b is also the measure from centres of circles B/C diameter of circle of circle B below centre of circle B |

|

Circle E. |

Centre: Radius: |

intersection of two arcs with radius b, one with centre at centre of circle A, the other with centre at b above centre of circle A (or, intersection of radius of 1/3 of circle A with arc having centre of circle A and radius b) 1/2b (its centre to (horizontal) midline of circle A) |

Robert Stevick

Seattle

14 July 2005