Late Medieval Window Tracery in 3D

Text and Models by Seán Sourke

Overview

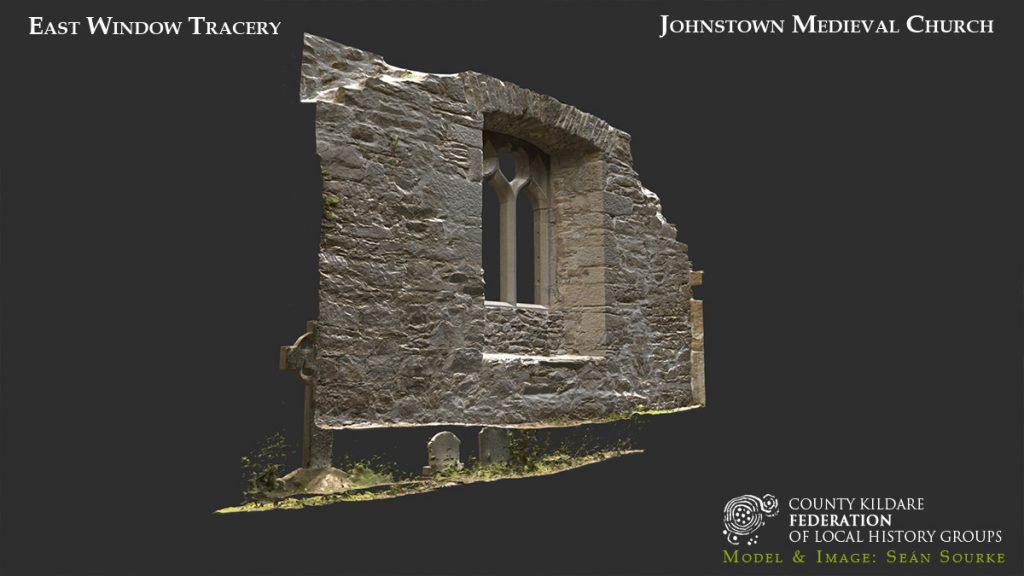

Johnstown Church (National Monument KD019-014001-)

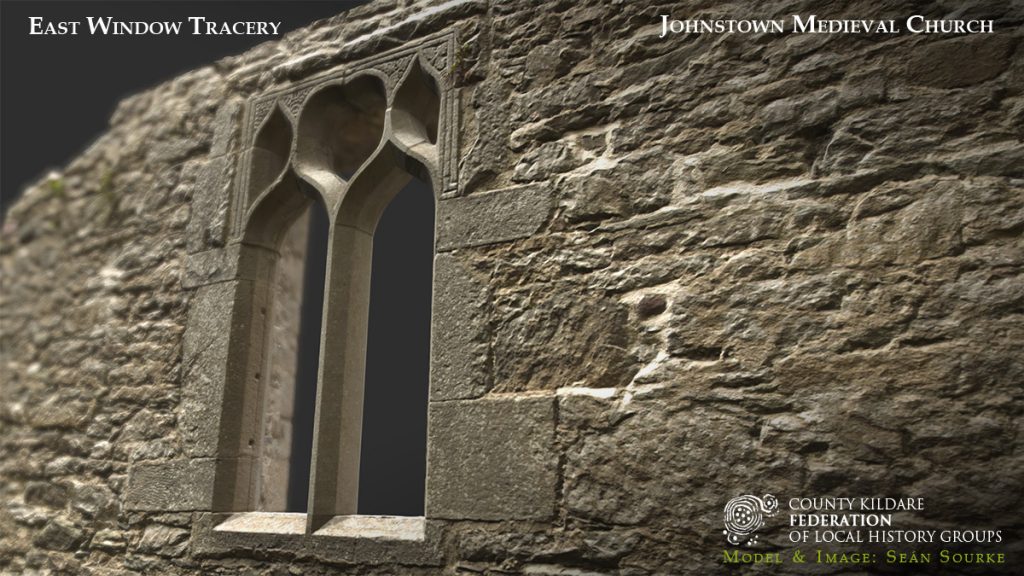

The east window of the ruined medieval church of Johnstown, Naas, Co. Kildare.

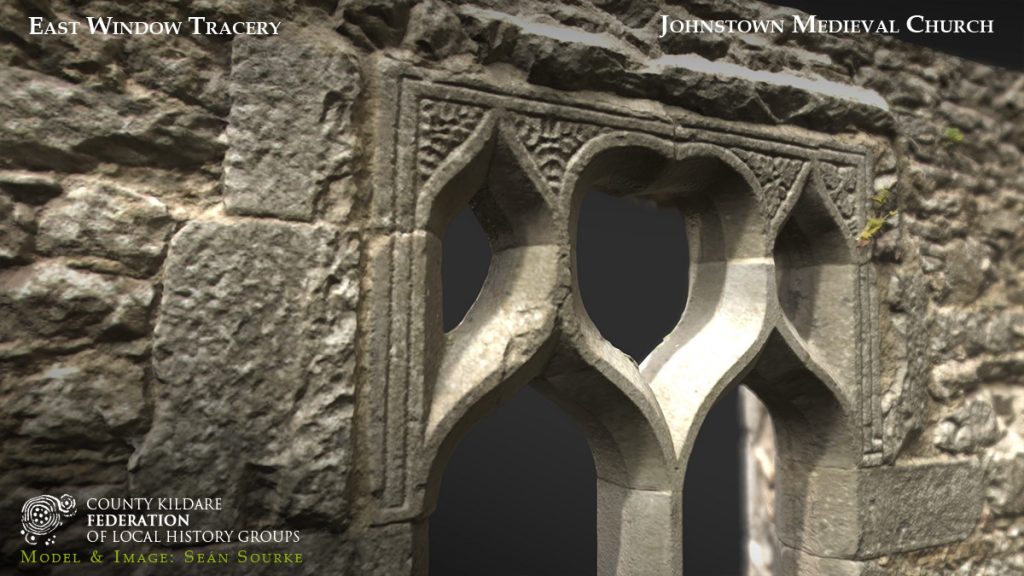

The late medieval window tracery was reconstructed in the early 1980s with a new mullion and central arch section created to complete the ogee-headed twin-lights. Externally the spandrels of the smaller upper ogee openings are carved with a leaf motif, outside of which are incised double lines forming a border. Traces of a very damaged hood moulding can be seen surrounding this upper section. Deep chamfers (both internally and externally) run along the edges of the window openings from the ogees down the side jambs, mullion, and across the sill, all carved on the individual dressed stones making up the window surround.

The church contains a late medieval grave slab known as the Flatesbury Stone, an annotated model of which can be viewed here: K3D – Flatesbury Stone

The church was owned by the Knights Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem throughout the late middle ages and it is thought that this gave rise to the village name of Johnstown.

NOTE: This model requires good bandwidth and a reasonably powerful computer to view successfully, as the download size is 280MB. Alternatively, you can view images with annotations in the section below the model.

Annotations on the Model

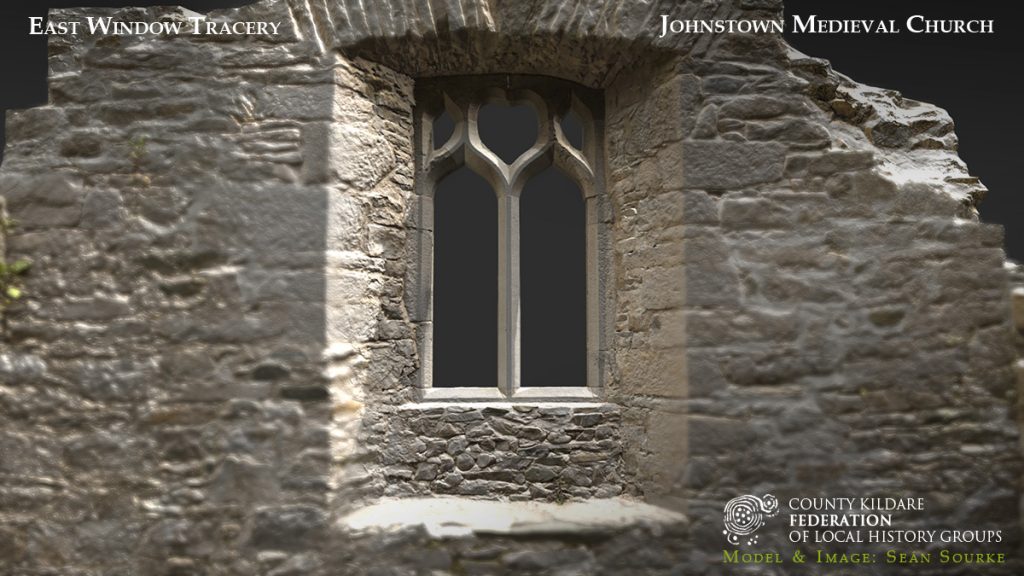

1. Late Medieval Window Tracery

The east window of the medieval church of Johnstown is carved from limestone sections that fit together to make up the tracery. The widow was reconstructed in the 1980s from the remaining original fragments and two newly carved stones commissioned to replace the missing pieces.

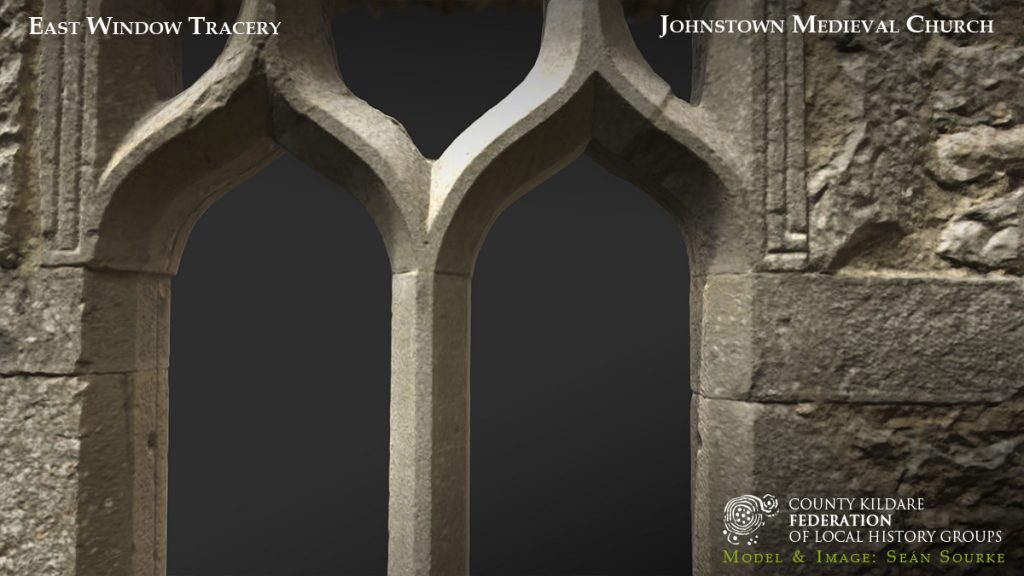

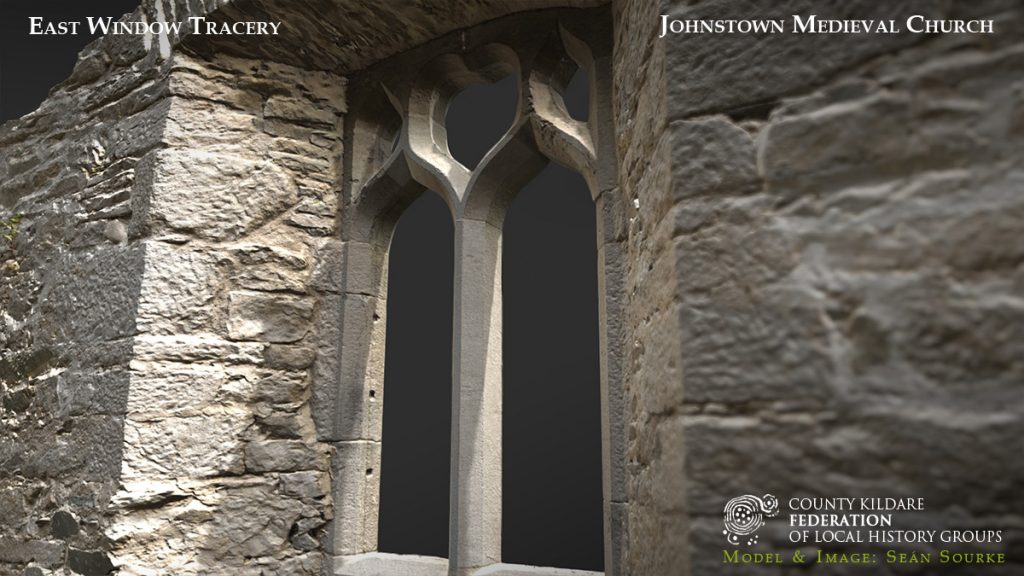

2. Ogee-Headed Twin-Lights

The two large twin-lights (two window openings divided by a vertical mullion) are enclosed by ogee arches.

An ogee is a pointed arch made up of two S-curves. This method of adding interest to a window light was introduced to Ireland in the early 14th century. It became an extremely popular motif and was often elaborated (from c. 1400 onwards) by decorative spandrels (as here), cusps, and hood-mouldings. It remained a popular style right up to c. 1600.

3. Reconstruction

Two replacement stones were carved in the 1980s to reinstate and complete the central section of the window.

The modern pieces consist of the mullion and a curved section that completes both ogee heads of the twin-lights and joins them to the upper smaller ogee headed openings and the central heart shaped opening.

A partial Y-shaped piece of original ogee tracery that corresponds in material, form, and proportion to this window’s tracery, and may have been part of this widow, is now embedded into the much altered walls of the nave.

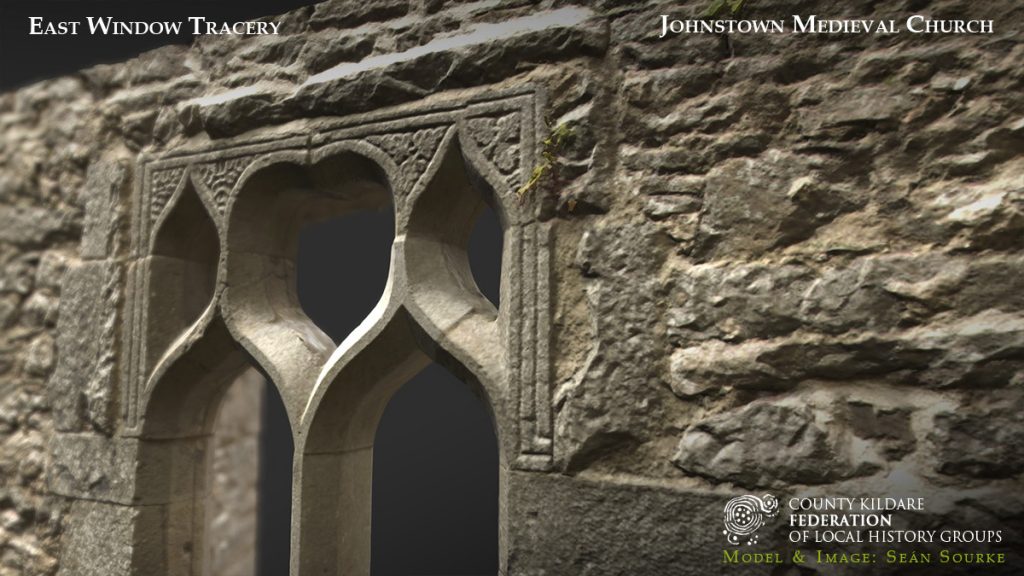

4. Carved Spandrels

Trefoil foliage motifs are carved within the spandrels above the window openings. Around these are two incised lines that form a border enclosing the upper window tracery.

A limestone architectural fragment embedded into the south wall of the nave to form a recess has a round-arched opening with the same style foliage motifs carved in its spandrels, which are also surrounded by double incised lines forming a border. This stone, of the same material and style, is undoubtedly by the same mason/workshop and of the same construction period.

5. Hood-Mouldings

A Hood Moulding (or Dripstone) is a carved stone (or stones) with a projecting element that runs horizontally above a window and partially down each side vertically – often as far as the springing of an ogee arch.

They commonly accompany twin-light ogee-headed windows of the period from c. 1400-1600. Their purpose was to deflect rain-water away from the window.

Slight traces of a hood-moulding remain on this window. They are to be found only on the two dressed stones framing the left side of the upper window. The moulding is severely damaged and is only discernible as a rough raised area along with traces of a right-angled return terminal on the lower stone – located on the same level as the springing of the ogee arches. The rest of the moulding is missing.

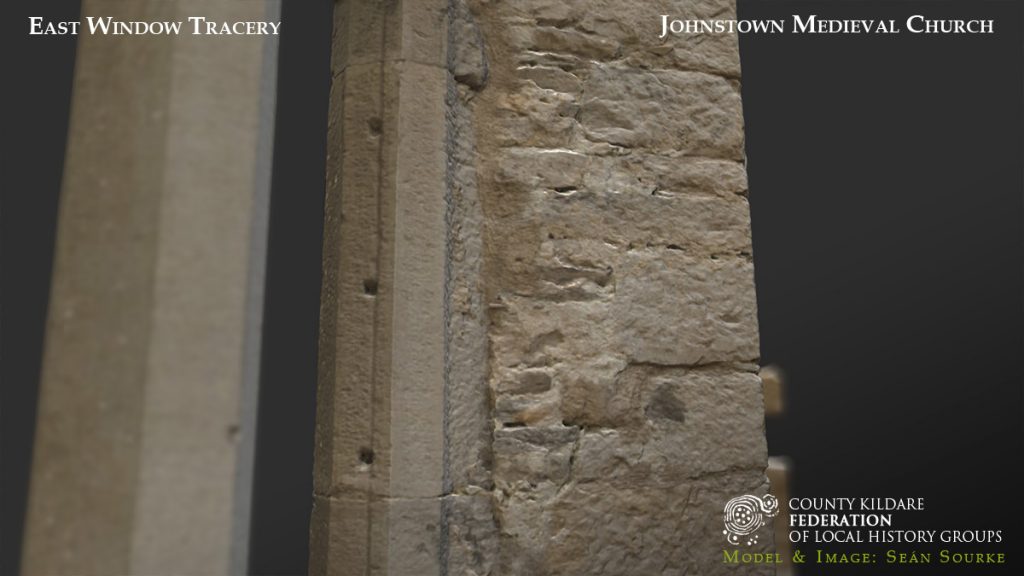

6. Window Dressings

The stone dressings that form the window openings are individually cut and designed to fit neatly together forming the whole window surround.

In contrast to the finely cut and smooth surfaces that form the tracery, the surfaces of the same stones where they face into the walls are dressed roughly and left irregular in order to bond into the masonry of the walls.

7. Original Features

The rebates carved to receive the leading of the glass panes are still crisply defined on the original stonework.

The three deeper square cavities visible here are to hold the metal cross bars that would have supported and protected the leading.

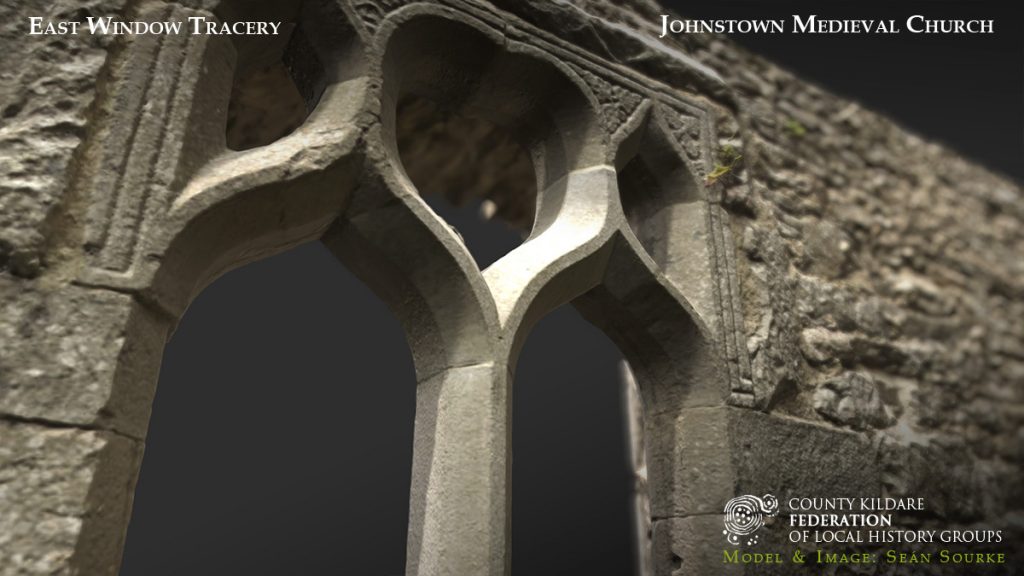

8. Heart-shaped Opening

The most striking feature of the window is this top central light.

A common late medieval tracery configuration was to divide a window into two large twin-lights, with two smaller lights above placed either side of a central light.

However, such windows were usually within a pointed arch dressing. The upper central light was normally circular (and often cusped forming a quatrefoil), a lozenge, or sometimes a trefoil opening, and commonly extend higher than the two side lights to fill the space within a pointed arch.

Here, however, the flat-topped design of the window dressing restricted the space available and the unusual solution (if the window has been reconstructed in its original configuration) was this heart-shaped light.

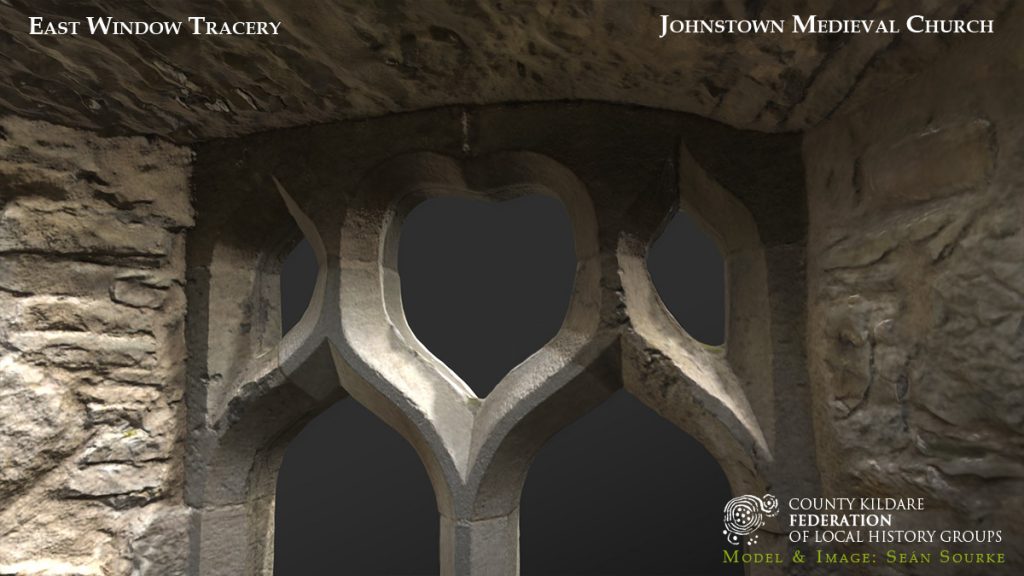

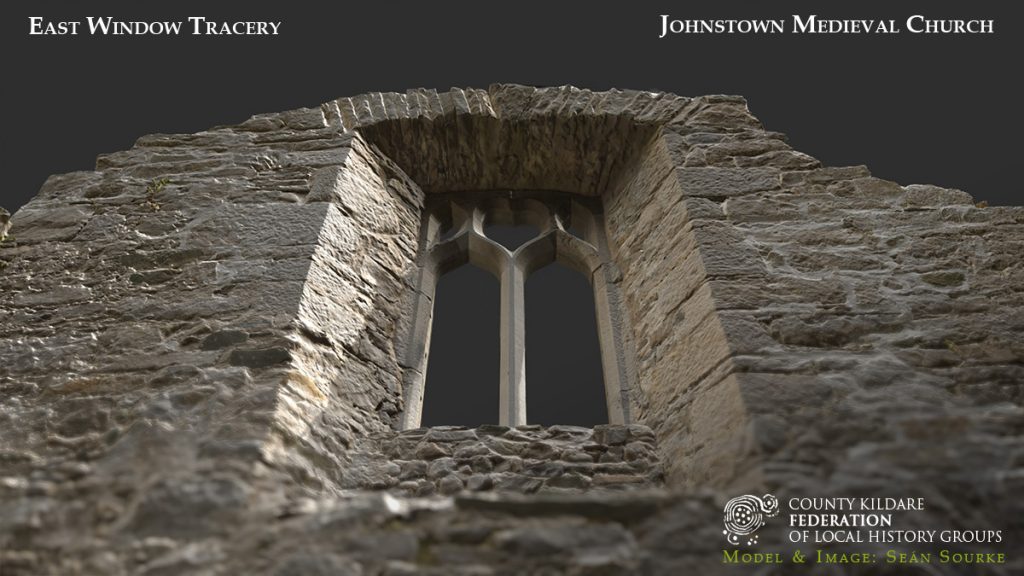

9. Internal Splays

A common feature of window openings throughout the medieval period was the internal splaying of walls to allow for the maximum amount of light to enter into the interior.

The walls would have originally been rendered and whitewashed.

10. Segmental Arch

A segmental arch supports the wall above the window internally. Segmental arches were used throughout the period c. 1200-1500.

11. Ground Levels

This model, which takes a section though the east end of the church, reveals the considerable difference in ground level between the interior of the church and the exterior at the east gable. The ground immediately outside the east gable wall also falls away from the building.

These features are likely caused by a combination of historic rubble accumulation from fallen church masonry and centuries of burials within the church.

A Moonlit Simulation

NOTE: This model requires good bandwidth and a reasonably powerful computer to view successfully, as the download size is 305MB. Alternatively, you can view images with annotations in the section below the model.